Reflections on the Redneck Riviera

Rhes Low reflects on vacations to the Alabama Gulf Coast and how before it grew into one of the South's top beach destinations, it was a rural slice of paradise.BY RHES LOW

The bulk of our lives is spent in places doing and working and surviving. Then there are the special places where we live—truly live. Orange Beach, Alabama, is where I live. I have made a life in Oxford, a place I adore. If I’m lucky, I will continue to do so. That said, not a day goes by I don’t long for OBA—a relatable feeling for anyone who’s ever lived in Oxford, especially those who’ve left it.

I’m not from Orange Beach, Alabama, and I’ve never been considered a local, though I humbly and earnestly strive to be recognized as one. It’s my place of rejuvenation, exploration, memories, peace. It is my Home, and it has changed exponentially, but so has everything else in my life.

I’ve never considered myself a “country boy,” nor have I ever been mistaken for one. Growing up in Laurel, I had my fair share of rural experiences but the majority of my youth was spent on the golf course and in the theatre. I went to Southern Methodist University in Dallas and lived the first half of my adult life in Los Angeles.

The farther I moved from home, the more I felt I’d missed out on benefits afforded one raised mud-bogging and hay-hauling.

I viewed the country life as one of self-sufficiency, masculinity, freedom, calm. Knowledge that provided understanding of how to live off the land, use a knife to skin an animal, cultivate and grow a garden, build something out of nothing.

I had become too gentrified.

For a long time, I was away from OBA. Then I moved to Oxford (still not the country), got divorced, lost a business, took some survival jobs, lost my Uncle Mitch (he was full of country attributes), lost Bigdaddy (my grandfather, also attributed with country knowledge)—all the stuff that hits us in one way or another as we get older.

In the wake of life, I began to venture back to OBA like I was being drawn there. I would pick up my son Friday after work, drive six hours, arrive at my family’s place in OBA around 12 a.m., go to sleep, spend Saturday playing, then drive back 6 hours on Sunday. On occasion, I’d do the same by myself.

Many of those Saturdays alone, I’d sit on the balcony of my parents’ plush condo and overlook the beautiful, often overcrowded, island-laden bay I grew up on. I’d peer to my left and try to envision my grandparents’ old beach house. Truthfully, it was more of a camp, thrown together as a semi-comfy escape from the elements when need be.

Now it’s an empty sandlot, demolished by a developer who went bankrupt before he could begin his extravagant high rise on the bay. Though the sandlot is super fun for my kids to fly kites, dig tunnels, shoot bottle rockets at each other, etc., it is and was a constant reminder that corporate gluttony had raped my childhood and I would never be able to go home again.

Of course, the offense did provide my grandparents with a substantial amount of money in which to live out their days (my grandmother is still doing so, vibrantly), not to mention their generosity in distributing a portion of the money to their children and grandchildren each Christmas. (Apologies to the developer for the judgmental “corporate gluttons” comment. Thank you for enhancing my bank account; screw you for bulldozing my childhood.) My journey of rejuvenation had begun via grasping for the past I knew, in that it’s the past, was simply gone. I just wanted to see it again.

Amid all the introspection and retrospection, one thing became apparent: I did grow up in the country. It turns out my “country” was a house on pylons, on an island, on a bay, in the middle of nowhere (at that time), called the Shuff Shack. The namesake of Mattie and Bernard Shuff, my grandparents. I long to go into great detail about every moment I remember spending my summers on Cotton Bayou but the limitations of this format will not allow such indulgences. It’s difficult to know where or how to begin.

I remember Beach Blvd lined with sand dunes, sea oats and the occasional humble house not yet destroyed by condos. I remember picking blackberries growing from the sand on the side of the house where Bigdaddy gave the Martins (a small, ugly, under-appreciated coastal bird) a three-story bird mansion in which to raise their young and provide hours of front-porch cocktail-hour entertainment as they are extremely territorial and constantly getting in fights.

I remember sand spurs, Cenchrus Longispinus. Evil plants that produce a small round ball with protruding spikes that slyly find a secure landing area by piercing the flesh on the underside of your foot and most certainly shrieking in evil joy, upon entry, as you shriek in pissed-off agony.

I remember the light blue dingy that washed ashore during a hurricane long before I was born. It became our swimming pool when our parents wanted to take a break from watching us in the bay, or when we grew exhausted from the endless possibilities bay frolicking provided. On occasion, the pool doubled as an aquarium of death for many an unsuspecting and often unidentified wetland creature.

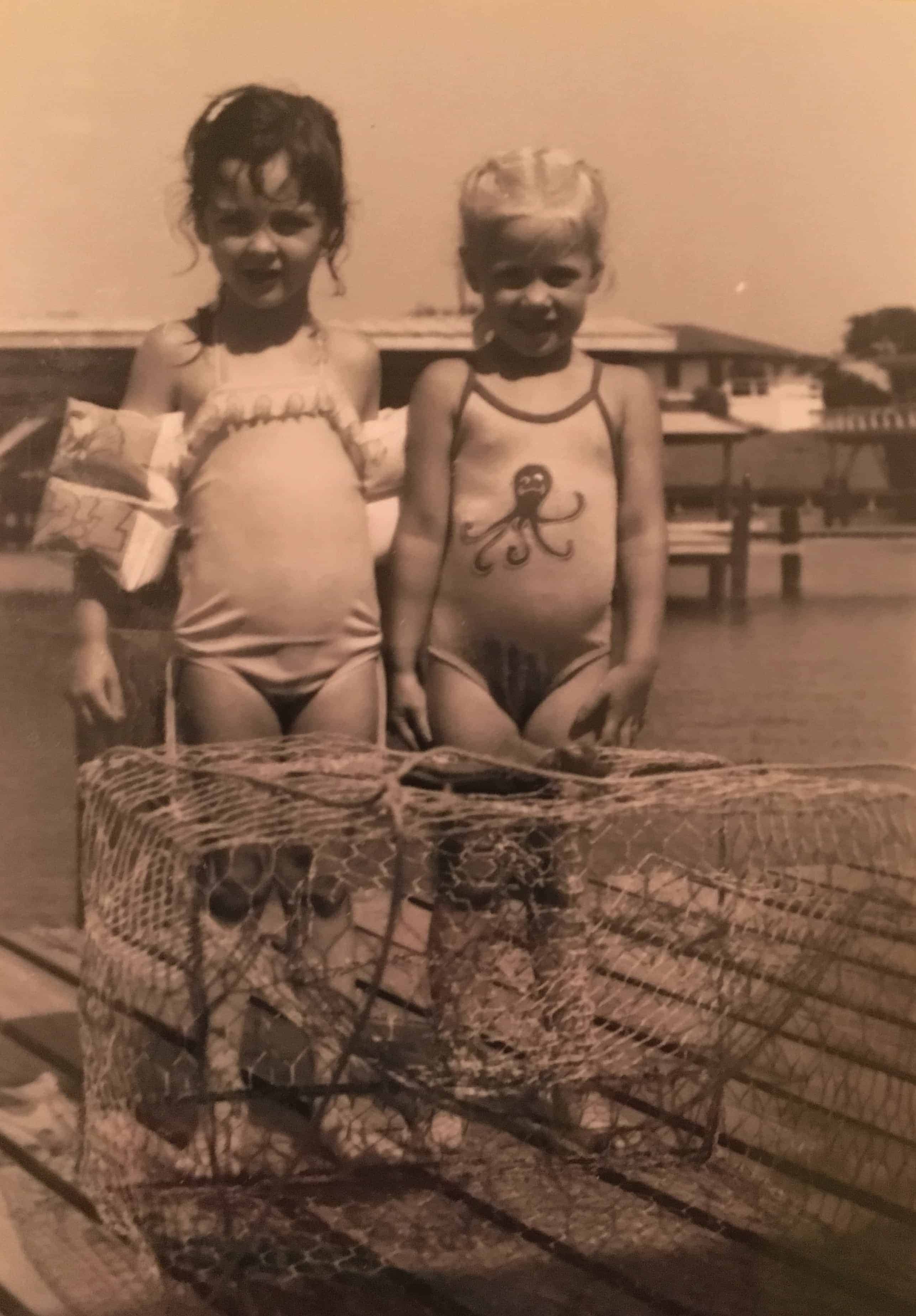

The benefit of living near a wetland area, for a kid, were the large patches of sea grass growing just off the shoreline of the bay. The grass housed many a creature that found its way into a simple dip net slung by a sunburnt child. (These were the days before sunscreen.) Daily, we pulled in shrimp, hermit crabs, minnows, baby crabs, sea horse, jellyfish in July, and the ultimate score: a big ole blue crab. This illustrious creature was a standard fixture at the lunch and dinner table, but to catch one in the grass was a feat revered by children and adults alike. An even greater accomplishment was grabbing an adult crab without getting pinched, pulling them from the dip net and presenting our conquest to parents or grandparents for consumption.

All tales aside, mullet are still plentiful and highly sought trophies from those of us pacing the pier with our cast nets. My mother was the mullet huntress queen. If I live to be 95, every time I see a cast net, I will think of my mother. She taught me how to put the corner of the salty net in my mouth to achieve the “perfect” throw and catch a plethora of baitfish or the prized dark shadow, Mullet. Not sure where she learned her technique, but a cast net can easily be thrown without putting a murky corner of it in your mouth. And yet, I will never stop putting slimy salt water in my mouth.

I grew up shrimping, fishing, spending all hours outdoors, sleeping sunburned in WWII-era bunk beds full of sand granules that attacked your crispy sensitive skin with a vicious ferocity, swimming to islands, running from storms, cultivating and consuming what nature provided. We were country. I was country. I am country.

The “Redneck Riviera” is a place where all social anomalies are equalized by a history of nature giving and taking as it sees fit. It is a place clad with 80 ft. yachts and small metal fishing boats running side by side. Where one can have lunch at a renowned southern eatery and catch a mullet from the pier to fry for dinner. Where families pull up crab traps full of succulent bounty in marinas filled with million-dollar fishing boats. In OBA, we exist in elegant condos and restaurants but we live in the ocean, the beaches and the bays. Even if I’m not there as often as I’d like, in our world of instant gratification and momentary newness, I’m glad my home will always be a small fishing village on the southernmost tip of Alabama with the history, people, creativity and ingenuity to grow but never change.